Whole grains have picked up plenty of rumours, from “they’re full of toxins” to “they’re packed with pesticides.” In reality, science shows they’re safe, nutritious, and recommended by health experts worldwide.

In this section, we address 10 common concerns that can turn into myths, with clear facts and simple explanations so you can enjoy them without second-guessing every bite.

![]() Fact

Fact

Whole grains are safe to eat, even though they may contain trace amounts of arsenic – a natural element found in soil, water, and air that can be absorbed as plants grow. There are two types: inorganic arsenic (more harmful) and organic arsenic. Chronic exposure to inorganic arsenic through diet or water can increase the risk of cancer of the skin, bladder, and lungs.1 However, risk assessment bodies like the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) monitor consumer exposure levels to arsenic to help the European Commission and Member States ensure that arsenic levels in whole grains in Europe remain within safe margins.

![]() Myth

Myth

It’s true that whole grains may contain slightly more arsenic than refined grains, since arsenic can build up in the outer layers (bran and germ), which are removed during refining. Rice, in particular, often has higher arsenic levels due to how it’s grown: unlike other cereals, rice is typically cultivated in flooded fields, where arsenic that naturally occurs in soil and irrigation water is more easily absorbed by the plant.2

To protect consumers from excessive exposure, a maximum level for arsenic in rice has been set by EU Regulation, at 0.25 mg/kg for brown rice (and 0.15 mg/kg for white rice). To give an order of magnitude: using EFSA’s reference point of the lowest dose that could be associated with increased risk of skin cancer after exposure to inorganic arsenic (0.06 µg/kg of bodyweight/day) and this maximum levels for inorganic arsenic in rice, an adult (70 kg) would reach that conservative reference after eating roughly 17 g/day brown rice (or 28 g/day of white rice). However, keep in mind that this is a benchmark for evaluating regulatory safety, not a recommended daily allowance. It’s meant to guide public health decisions, not to tell an individual “don’t exceed 17 g of rice today.” Further safety margins are built into any maximum levels set by regulatory authorities to minimise adverse health outcomes.

Switching to refined grains isn’t the solution, as it means losing the fibre, vitamins, and minerals that make whole grains nutritious and widely recommended. There are also effective ways to reduce arsenic exposure from rice:

![]() Why it feels true (even when it’s wrong)

Why it feels true (even when it’s wrong)

The myth misuses scientific risk, implying that because arsenic can be harmful in high doses, whole grains are unsafe in everyday amounts – when in fact, levels in Europe are far below any risk threshold. Another error is the “false choice fallacy:” presenting two options as the only ones available, forcing someone to choose between extremes rather than considering other options. By focusing on one potential risk (arsenic) while ignoring overall health benefits (fibre, vitamins, and minerals), this myth creates a false choice.

![]() Fact

Fact

Whole grains are safe to eat and, like all foods, are tightly regulated for pesticide residues. Pesticides are commonly used in farming to protect crops from pests and disease. Small residues may remain on food after harvest, but these levels are strictly monitored and regulated in Europe by Member States and bodies like the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Further safety margins are built into any maximum levels set by regulatory authorities to ensure safe levels of intake. Whole grains remain a key part of a healthy diet, providing essential nutrients that refining removes, like fibre, iron, magnesium, and B vitamins.

Find here a database of used pesticides in the EU and levels of pesticide residues on particular food products.

![]() Myth

Myth

While it’s true that whole grains may retain slightly more residues than refined grains because the outer layers of the grain (bran and germ) are kept intact and this is where the highest concentrations of pesticide residues are found, this doesn’t automatically mean they contain harmful levels.4 EFSA concluded that there is a low risk to consumer health from the estimated exposure to pesticide residues in the foods tested.5 The European Union has some of the strictest pesticide regulations in the world, including maximum residue levels (MRLs) (the highest level of pesticide residue that is legally allowed in or on food products) that are regularly reviewed and updated. Food products that exceed MRLs trigger legal sanctions and enforcement actions. The possible risk posed by pesticides from whole grains doesn’t outweigh the known nutritional benefits of eating whole grains.6

![]() Why it feels true (even when it’s wrong)

Why it feels true (even when it’s wrong)

This myth takes a small truth—that whole grains often contain slightly higher pesticide residues than refined grains since the outer layers are retained—and turns it into a sweeping (and misleading) claim. It suggests that avoiding whole grains is safer, which ignores both the health benefits of whole grains and the safety controls already in place.

This myth also relies on scare tactics, implying that any pesticide residue is harmful, regardless of dose. In reality, pesticides are strictly regulated, and residue levels in EU grains are consistently far below the threshold of concern. These regulations exist precisely because pesticides are toxic at high doses, but at the controlled levels found in food, they do not pose a health risk. Moreover, pesticides play an important role in ensuring the safety, integrity, and availability of food by protecting crops from pests and disease.

It also taps into the “natural is safer” fallacy, which wrongly assumes that anything artificial (like synthetic pesticides) is automatically dangerous. In practice, what matters is that residue levels remain well within the authorised safety margins established to protect consumers.

![]() Fact

Fact

Whole grains are very beneficial for your digestive system and overall health. They’re rich in fibre, which is crucial for our gut microbiome—the trillions of beneficial bacteria living in your intestines. These fibres act as food for these good bacteria, helping them thrive and produce beneficial compounds like short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). They protect our health by improving insulin sensitivity and ensuring lower levels of glucose and lipids in our bloodstream. Over the long term, this might improve energy balance, which indirectly protects against cardiovascular diseases, obesity and type 2 diabetes.7,8,9

Whole grains are more complex than refined grains and are promoted as part of a healthy and sustainable diet, largely due to their high content of indigestible carbohydrates (dietary fibres) and higher levels of vitamins, minerals, and other nutrients.10

![]() Myth

Myth

This idea that whole grains are a common culprit for bloating and gas often stems from the fact that whole grains contain fibres and certain carbohydrates that are not fully digested in the small intestine. When these reach the large intestine, gut bacteria ferment them, which can produce gas. However, this natural process is usually a sign that your gut bacteria are hard at work, not that whole grains are inherently problematic.

![]() Why it feels true (even when it’s wrong)

Why it feels true (even when it’s wrong)

The fallacy here is a misattribution. The natural fermentation process that occurs when gut bacteria break down fibres in whole grains is mistakenly perceived as a negative side effect, rather than a beneficial one. While some individuals might experience temporary discomfort when first increasing their fibre intake, this often subsides as their gut adapts. For those with specific sensitivities, like Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), certain components in grains, such as fructans, might trigger adverse symptoms.10 However, for the general population, whole grains are an important part of a balanced diet. If you experience persistent or severe digestive issues, consult a healthcare professional (e.g., GP or registered dietitian/nutritionist) for personalised advice.

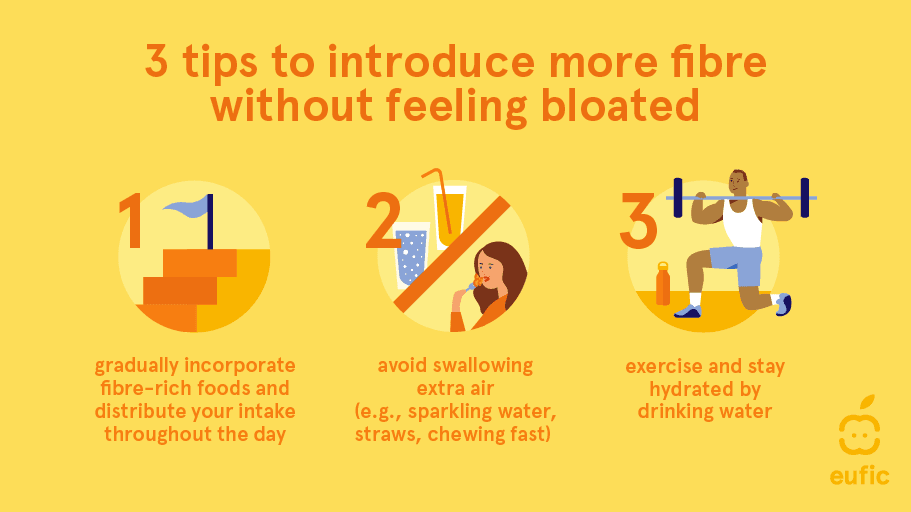

Before cutting out whole grains from your diet, there are a few tips & tricks you can do to retrain your gut to embrace these fibre-rich foods and ease the bloat:

![]() Fact

Fact

Anti-nutrients are chemicals that are found in plant-based foods that can interfere with how your body absorbs nutrients. In whole grains, the main ones are lectins, oxalates, phytates, and tannins. Although evidence is limited, some suggested implications of these anti-nutrients include altered gut function and inflammation (lectins), reduced absorption of calcium (oxalates), reduced absorption of iron, zinc, and calcium (phytates), and iron (tannins).

But here’s the important part: in a balanced diet, this effect is minimal and doesn’t make whole grains “nutritionally worthless.” In fact, whole grains contribute significantly to daily nutrient intakes, and their benefits far outweigh any potential minor reduction in mineral absorption.11

![]() Myth

Myth

The myth suggests that compounds like phytates, lectins, oxalates, and tannins in whole grains hinder nutrient absorption, making them unhealthy. This oversimplified view, for example, ignores the difference in how these compounds behave in isolation versus within a complex food matrix:

![]() Why it feels true (even when it’s wrong)

Why it feels true (even when it’s wrong)

The misconception relies on the fallacy of isolation. While antinutrients can bind minerals in a lab test, that doesn’t mean eating whole grains leads to deficiencies in real-life diets, especially in Europe, where diets are highly diverse. Research from large populations eating whole grains over multiple years and trials of people replacing refined grains with whole grains consistently shows that whole grains improve overall nutrient intake and health outcomes.12,13

![]() Fact

Fact

Whole grains are rich in fibre, which supports digestive health. But for some people with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) or other gut sensitivities, certain grains can trigger symptoms like bloating, discomfort, or changes in bowel habits. Especially wheat, rye, and barley have been linked to these symptoms in sensitive people.14

Guidelines recommend that it may be helpful to limit the intake of high-fibre foods (such as whole grain or high-fibre flour and breads, cereals high in bran, and whole grains such as brown rice) for those with IBS, but that doesn’t mean all whole grains are off the table.15 A gluten-free diet is often used to alleviate symptoms for those with IBS, but gluten isn’t always what causes the discomfort. Research suggests that symptom relief is achieved not from removing gluten specifically, but from excluding wheat itself, indicating that other wheat components—such as fructans, amylase-trypsin inhibitors, and lectins—are likely responsible for triggering digestive discomfort.14

Many people with IBS tolerate other nutritious whole grains such as spelt, oats, quinoa, rice, and corn. Spelt bread, for example, contains much lower levels of fructans than standard wheat bread. Observe which grains cause symptoms for you, identify the quantity of these products that trigger discomfort, and try to keep as much variety in your diet as possible.

![]() Myth

Myth

It’s a common belief that people with IBS should cut out all whole grains, especially those containing gluten. While some people do report relief after avoiding wheat-based products, studies show that not everyone benefits from going gluten-free. In fact, many IBS patients who cut out gluten may actually be responding to the reduction of wheat and its other components, not gluten itself. Avoiding all whole grains can unnecessarily restrict the diet and lead to lower fibre and nutrient intakes, which may worsen gut health in the long run.

![]() Why it feels true (even when it’s wrong)

Why it feels true (even when it’s wrong)

This myth oversimplifies a complex condition. It assumes that because wheat may cause symptoms, all grains must be harmful. In reality, tolerance is highly individual: some people may react strongly to wheat but can enjoy oats, rice, quinoa, or spelt without problems.

Another fallacy is focusing solely on gluten as the “villain.” Research shows that other wheat compounds, like fructans, are often the real triggers for IBS symptoms. By blaming gluten alone, people may unnecessarily adopt restrictive diets that cut out valuable whole grains that could otherwise support digestive health.

![]() Fact

Fact

Whole grains contain all three parts of the grain: the bran, germ, and endosperm. This makes them higher in fibre, vitamins, and minerals than refined grains and they also help to reduce our risk of developing chronic diseases. That’s why dietary guidelines across Europe recommend swapping white, refined products for whole grain versions.

But here’s the catch: a darker colour doesn’t guarantee a product is whole grain. Bread, crackers, or cereals can look brown simply because of added molasses, malt, or caramel colouring. True whole grain products can be identified by:

Another easy trick? Use the 10:1 carbohydrate-to-fibre ratio: for every 10 g of carbs, a product should have at least 1 g of fibre.

![]() Myth

Myth

A brown colour doesn’t guarantee it’s a whole grain product. In fact, they may still use mostly refined flour. Bread can be made mostly from refined white flour and simply coloured brown with molasses or caramel. Likewise, products described as “brown,” “multi-grain,” or “100% wheat” often look wholesome but may still lack the full benefits of whole grains.

![]() Why it feels true (even when it’s wrong)

Why it feels true (even when it’s wrong)

This myth falls into the trap of visual bias: judging healthiness based on colour. Brown bread looks “healthier” than white bread, so it’s easy to assume it’s whole grain. But colour can be misleading. What really matters is whether the product contains the entire grain kernel, not whether it looks dark.

![]() Fact

Fact

Gluten is a protein found in wheat, barley, and rye. That means whole wheat bread, whole grain barley, and whole rye products, and any other whole grain products containing these grains all contain gluten. These should be avoided by people with coeliac disease or gluten sensitivity.

But many whole grains are naturally gluten-free, including: corn, rice (brown, red, black, and wild varieties), quinoa, buckwheat, millet, amaranth, teff, sorghum, and certified gluten-free oats. These gluten-free grains are safe and nutritious options that add variety, flavour, and important nutrients like fibre, vitamins, and minerals to your diet.

Unless you have a diagnosed gluten-related condition, there’s no evidence that cutting out gluten is healthier for you. In fact, some gluten-free products contain more sugar, fat, or salt than their regular counterparts.

![]() Myth

Myth

Not all whole grains are high in gluten. There are many different whole grains to choose from and include as part of your diet. This myth lumps all whole grains together, assuming they all act like wheat. While wheat, rye, and barley do contain gluten, many other grains don’t. By painting all whole grains with the same brush, this myth wrongly encourages people to avoid a wide variety of safe and nutritious foods.

![]() Why it feels true (even when it’s wrong)

Why it feels true (even when it’s wrong)

This myth makes the mistake of overgeneralisation, taking the fact that some grains contain gluten and applying it to all grains. In reality, gluten is only found in a few types. Avoiding all whole grains because of gluten is like avoiding all fruit because you’re allergic to strawberries—it cuts out far more than necessary.

![]() Fact

Fact

Carbohydrates are our body’s main energy source, fuelling the brain, muscles, and all cells. Eating carbs doesn’t automatically cause weight gain. What matters is the overall balance between calories in and calories out.

Whole grains provide fibre, vitamins, minerals, and protective plant compounds that support satiety, stable energy, and long-term health. Fibre helps us feel fuller for longer periods after a meal. This means we eat less food, which could lead to a reduction in overweight and obesity. There are data to suggest that eating whole grains can lead to slightly reduced body weight in obese/overweight populations compared to non-whole grain diets.16

International agencies including the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) recommend that adults get 45–60% of their daily calories from carbohydrates, with as little added sugar as possible and at least 25 g of dietary fibre per day.17 Cutting out whole grains runs directly against these evidence-based recommendations.

![]() Myth

Myth

Whole grains don’t automatically cause weight gain because they’re high in carbs. This myth is reinforced by the popularity of low-carb and keto diets. Advocates of such diets argue that carbs drive weight gain by increasing insulin, which promotes fat storage. But scientific evidence doesn’t support this theory:18

While refined carbs and sugary drinks can contribute to excess calories, whole grains are a different story. They provide fibre, vitamins, and minerals that help regulate appetite and support healthy digestion.

![]() Why it feels true (even when it’s wrong)

Why it feels true (even when it’s wrong)

The “carbs = fat gain” myth relies on the carbohydrate–insulin model, which selectively cites evidence and ignores the bigger picture. Yes, insulin helps store fat temporarily, but fat gain only occurs if total calories consistently exceed what the body uses. Studies show that when calorie and protein intake are controlled, low-carb diets don’t lead to greater fat loss than diets with more carbohydrates.20,21

Another fallacy is confusing water loss with fat loss. The rapid results many see on keto come mostly from glycogen and water being flushed out, not actual fat reduction. Over time, weight loss typically plateaus, and health risks may increase due to nutrient deficiencies and whole grains being displaced with foods high in saturated fat.22

Finally, this myth fails to distinguish between refined carbs (like sugary drinks and white bread, which are linked to weight gain) and nutritious carbs (like whole grains, fruits, and legumes, which support healthy weight and lower disease risk). In fact, diets low in whole grains are the leading dietary risk factor for ill-health, disability, and early death in Europe.23

![]() Fact

Fact

Inflammation isn’t always a bad thing. In fact, it’s the body’s natural defence mechanism: when you cut your finger or fight off an infection, inflammation helps heal wounds and protect against harmful microbes. The problem comes when inflammation doesn’t switch off and becomes chronic. Chronic, low-grade inflammation has been linked to obesity, cancer, and cardiovascular diseases.24

Multiple large-scale studies demonstrate that eating whole grains lowers markers of chronic inflammation:25

Why? Whole grains are rich in fibre, phenolic acids, and other bioactive compounds. These not only improve gut microbiota but also produce metabolites that help dampen inflammatory pathways.26

![]() Myth

Myth

Whole grains don’t cause inflammation. This myth often points to “anti-nutrients” like gluten or lectins, claiming they irritate the gut and set off inflammation. While some people with coeliac disease or wheat allergy must avoid gluten, for the vast majority, these claims are misleading. In normal amounts and as found in whole, cooked grains, lectins and phytates are not harmful—and in many cases, they may even have protective health benefits.11

By focusing only on theoretical risks, this myth ignores the strong evidence showing that whole grains reduce inflammation and promote long-term health.

![]() Why it feels true (even when it’s wrong)

Why it feels true (even when it’s wrong)

The idea that whole grains “cause inflammation” cherry-picks isolated lab studies on compounds like gluten or lectins, and then generalises those findings to everyone. But human studies overwhelmingly show the opposite: higher whole grain intake is linked to lower inflammation and disease risk.

Another fallacy is confusing special cases with the rule. Yes, people with coeliac disease must avoid gluten-containing grains, but this doesn’t apply to the general population. As recommended by almost all dietary guidelines, whole grains are part of a healthy, balanced dietary pattern that helps promote overall health.

![]() Fact

Fact

Whole grains, whether in a slice of whole grain bread, a bowl of oats, or a box of whole grain pasta, are consistently linked to better health outcomes. Research shows that eating 50 g of whole grains daily is linked to a 25% lower incidence of type 2 diabetes, 20% reduced risk of cardiovascular mortality, 12% reduction in cancer mortality, and a 15% decrease in total mortality.13 This holds true whether the grains come from a bag of brown rice, a packet of whole grain crackers, or a loaf of rye bread.

Yes, some whole grain foods are packaged and may fall under the NOVA “ultra-processed” (UPF) classification, which defines certain foods as containing little of no whole foods and that are formulations of ingredients made by a series of industrial processes and/or containing food additives. For example, many commercially produced whole grain breads contain additives to improve texture, taste, and shelf life. These additives may include emulsifiers, dough conditioners, and stabilisers – processed ingredients that are common in ultra-processed foods. All food additives have been thoroughly tested, classified as safe by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and approved for use by the European Commission and Member States.

![]() Myth

Myth

Avoiding all packaged whole grain foods because they’re ultra-processed could unnecessarily restrict your diet. While some UPFs may contribute to poor health outcomes, other UPFs can be nutrient-rich and fit into a balanced diet, such as whole grain bread, vegetable-based sauces, and (fortified, low-sugar) plant-based dairy alternatives. Certain groups, such as animal products, sauces, spreads and condiments, and artificially and sugar-sweetened beverages, have been found to be associated with increased disease risks, while other groups, such as breads and cereals, have been associated with lower disease risks.27 This might be explained by the fibre content of such products. What matters most is what’s inside the package. For example:

A key to making more informed food choices is to check the ingredients list and the nutritional information: does it contain mostly whole grains, with limited added sugar, salt, and fat? If yes, it can absolutely fit into a balanced diet.

![]() Why it feels true (even when it’s wrong)

Why it feels true (even when it’s wrong)

This myth works through guilt by association: because some ultra-processed foods are linked to poor health outcomes, all foods in this category must be harmful. But nutrition science doesn’t work that way. The health effects of a food depend on its nutrient content, role in the diet, and overall dietary pattern, not simply whether it comes in a package or is “processed.” Dietary guidelines across Europe encourage eating more whole grains, including packaged versions like bread, pasta, or breakfast cereals, because they help fill fibre and other nutrient gaps in our diets.

1.

EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM), Schrenk, D., Bignami, M., Bodin, L., Chipman, J. K., del Mazo, J., … & Schwerdtle, T. (2024). Update of the risk assessment of inorganic arsenic in food. EFSA Journal, 22(1), e8488.

2.

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), Arcella, D., Cascio, C., & Gómez Ruiz, J. Á. (2021). Chronic dietary exposure to inorganic arsenic. EFSA Journal, 19(1), e06380.

3.

Menon, M., Dong, W., Chen, X., Hufton, J., & Rhodes, E. J. (2021). Improved rice cooking approach to maximise arsenic removal while preserving nutrient elements. Science of the Total Environment, 755, 143341.

4.

Hakme, E., Hajeb, P., Herrmann, S. S., & Poulsen, M. E. (2024). Processing factors of pesticide residues in cereal grain fractions. Food Control, 161, 110369.

5.

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), Carrasco Cabrera, L., Di Piazza, G., Dujardin, B., Marchese, E., & Medina Pastor, P. (2025). The 2023 European Union report on pesticide residues in food. EFSA Journal, 23(5), e9398.

6.

Thielecke, F., & Nugent, A. P. (2018). Contaminants in grain—a major risk for whole grain safety?. Nutrients, 10(9), 1213.

7.

Capuano E (2017). The behavior of dietary fiber in the gastrointestinal tract determines its physiological effect. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 57:16, 3543-64

8.

European Commission (2019). Food-Based Dietary Guidelines in Europe.

9.

Dalile B, Van Oudenhove L, Vervliet B, and Verbeke K (2019). The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota–gut–brain communication. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology and Hepatology 16, 461-78

10.

Seal, C. J., Courtin, C. M., Venema, K., & De Vries, J. (2021). Health benefits of whole grain: Effects on dietary carbohydrate quality, the gut microbiome, and consequences of processing. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 20(3), 2742-2768.

11.

Petroski, W., & Minich, D. M. (2020). Is there such a thing as “anti-nutrients”? A narrative review of perceived problematic plant compounds. Nutrients, 12(10), 2929.

12.

Marshall, S., Petocz, P., Duve, E., Abbott, K., Cassettari, T., Blumfield, M., & Fayet-Moore, F. (2020). The effect of replacing refined grains with whole grains on cardiovascular risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials with GRADE clinical recommendation. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 120(11), 1859-1883.

13.

Blomhoff, R., Andersen, R., Arnesen, E.K., Christensen, J. J., Enoroth, H., Erkkola, M., Guadanaviciene, I., Halldorsson, I.I., Hoyer-Lund, A., Lemming, E.W., Meltzer, H.M., Pitsi, T., Schwab, U., Siksna, I., Thorsdottir, I. and Trolle, E. Nordic Nutrition Recommendations 2023. Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers, 2023

14.

Radziszewska, M., Smarkusz-Zarzecka, J., & Ostrowska, L. (2023). Nutrition, physical activity and supplementation in irritable bowel syndrome. Nutrients, 15(16), 3662.

15.

Recommendations | Irritable bowel syndrome in adults: diagnosis and management | Guidance | NICE

16.

Wang, W., Li, J., Chen, X., Yu, M., Pan, Q., & Guo, L. (2020). Whole grain food diet slightly reduces cardiovascular risks in obese/overweight adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC cardiovascular disorders, 20, 1-11.

17.

EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition, and Allergies (NDA). (2010). Scientific opinion on dietary reference values for carbohydrates and dietary fibre. EFSA Journal, 8(3), 1462.

18.

Hall KD, et al. (2022). The energy balance model of obesity: beyond calories in, calories out. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 115(5), 1243-1254.

19.

Kirkpatrick, C. F., Bolick, J. P., Kris-Etherton, P. M., Sikand, G., Aspry, K. E., Soffer, D. E., … & Maki, K. C. (2019). Review of current evidence and clinical recommendations on the effects of low-carbohydrate and very-low-carbohydrate (including ketogenic) diets for the management of body weight and other cardiometabolic risk factors: a scientific statement from the National Lipid Association Nutrition and Lifestyle Task Force. Journal of clinical lipidology, 13(5), 689-711.

20.

Hall, KD, et al. (2016). Energy expenditure and body composition changes after an isocaloric ketogenic diet in overweight and obese men. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 104(2), 324-333.

21.

Hall KD, et al. (2015). Calorie for calorie, dietary fat restriction results in more body fat loss than carbohydrate restriction in people with obesity. Cell metabolism, 22(3), 427-436.

22.

Batch JT, et al. (2020). Advantages and disadvantages of the ketogenic diet: a review article. Cureus, 12(8).

23.

IHME. (2021). Global Burden of Disease. Accessed 26 September 2025.

24.

Cifuentes, M., Verdejo, H. E., Castro, P. F., Corvalan, A. H., Ferreccio, C., Quest, A. F., … & Lavandero, S. (2025). Low-grade chronic inflammation: a shared mechanism for chronic diseases. Physiology, 40(1), 4-25.

25.

Milesi, G., Rangan, A., & Grafenauer, S. (2022). Whole grain consumption and inflammatory markers: a systematic literature review of randomized control trials. Nutrients, 14(2), 374.

26.

Khan, J., Gul, P., Rashid, M. T., Li, Q., & Liu, K. (2024). Composition of whole grain dietary fiber and phenolics and their impact on markers of inflammation. Nutrients, 16(7), 1047.

27.

Cordova, R., Viallon, V., Fontvieille, E., Peruchet-Noray, L., Jansana, A., Wagner, K. H., … & Freisling, H. (2023). Consumption of ultra-processed foods and risk of multimorbidity of cancer and cardiometabolic diseases: a multinational cohort study.

Learn to identify whole grain products, cook delicious meals, find practical tips for a smooth, gradual switch, and much more!